Working Papers

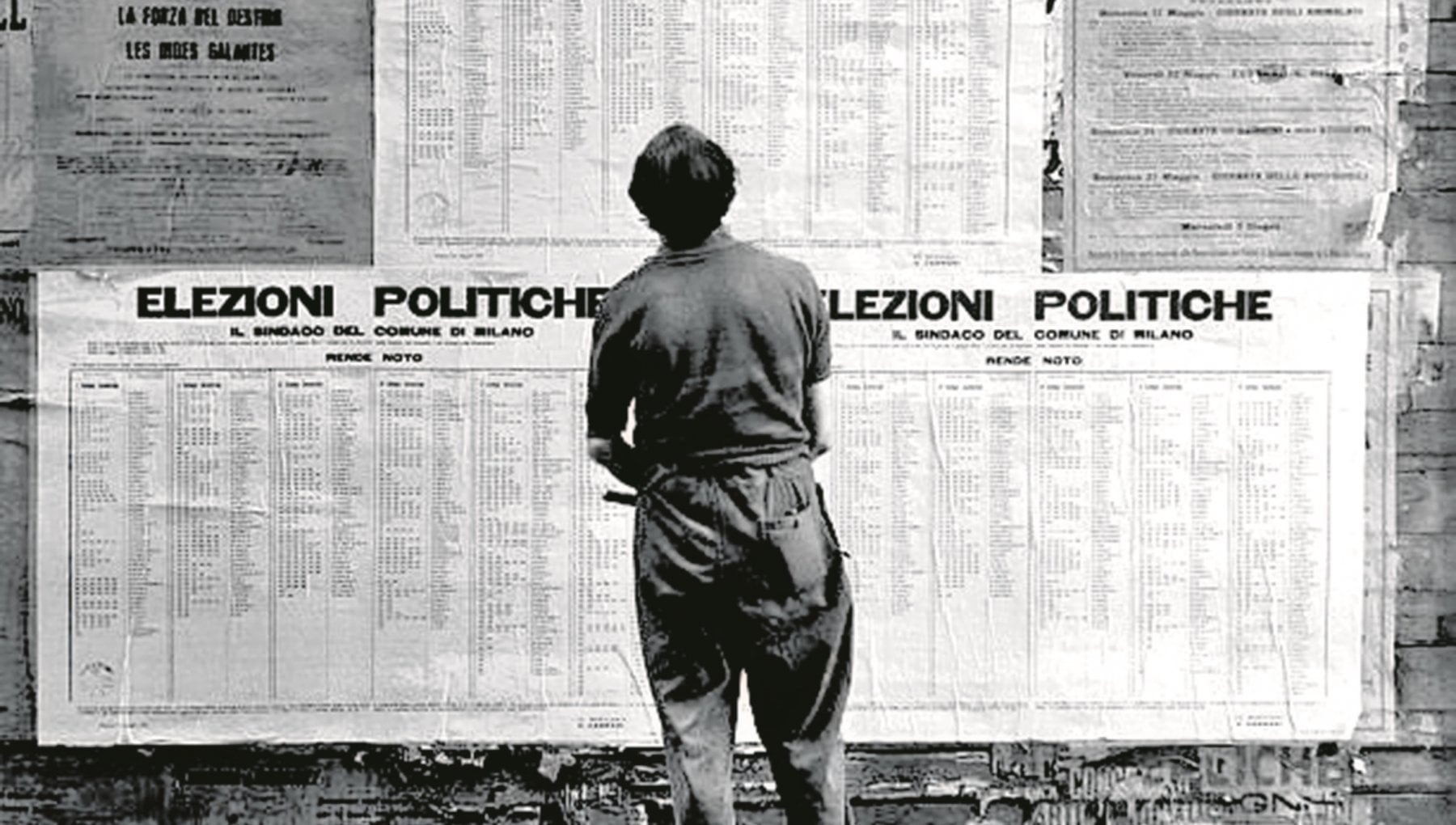

Community leaders often mobilize support for politicians in exchange for rents. Yet, this relationship can be contentious, as both actors might shirk on their commitments. Given this uncertainty, little is known about when and how politicians reciprocate the brokerage of community leaders. We argue that politicians exploit pre-existing personal connections with community leaders to overcome commitment problems and secure support. In turn, politicians provide rewards that increase the brokers' status. We illustrate this argument by investigating exchanges between Catholic bishops and Christian Democratic politicians in postwar Italy. We combine information on the renovation of Catholic churches with data on personal connections between politicians and bishops. Difference-in-differences estimates indicate that bishops mobilize support for connected politicians. Once elected, the latter reward connected bishops with investments in church renovations, especially when they compete under electoral rules that incentivize intraparty competition. These findings illustrate important conditions and mechanisms underpinning clientelistic relationships.

How does unequal representation affect policymaking? It is widely assumed that overrepresented districts exert greater influence over policy, yet isolating the effects of representation from underlying district characteristics remains both theoretically and empirically challenging. I argue that increased representation can independently bias policymaking via two channels: a mechanical effect, whereby increased representation raises a district’s probability of setting the agenda, and a behavioral effect, where legislators intensify their efforts due to intra-district competition. To test this, I leverage the quasi-experimental setting created by the electoral rule of the Italian Senate (1994-2006), which allowed districts with similar population sizes to elect either one or two senators. Using a regression discontinuity design and comprehensive data on bill (co-)sponsorship, I find evidence supporting both channels. Examining policy outcomes, I do not find that unequal representation yields distributive benefits, but I do find suggestive evidence of a broader legislative advantage.

This article argues that in a context of widespread clientelism and poverty, local public goods provision is a tool for mass patronage. Clientelistic incumbents under threat entice economically vulnerable voters into supporting the regime by creating jobs in the construction sector through infrastructural investments. The theory is tested using data on public works projects funded by the Cassa del Mezzogiorno, a massive place-based policy for the development of Southern Italy introduced after WWII. Empirically, I exploit within-politician shocks in competition induced by the electoral rule of the post-war Italian Senate. The results reveal that public works investments increase when Christian democratic senators are threatened in their own districts by the election of a communist senator, that this effect is particularly strong in areas characterized by low levels of employment, and that this distribution generates electoral returns.

Work in Progress

This article proposes a novel theory of minority status and support for supranational integration. We argue that the gap in status and opportunities between majority and minority individuals affects the evaluation of international institutions. Individuals whose socioeconomic status and opportunities are restricted because of minority traits are more dissatisfied with national institutions and more favorable toward supranational integration than their majority counterparts. We test our theory on the European Union, the most advanced case of regional integration. Using different operationalizations of minority status and an exact matching strategy, we demonstrate a robust positive association between minority status and support for supranational integration. Testing the mechanisms, we present evidence that integration in the host country and discrimination drive these effects.

Previous research on party preferences has assumed that individual partisanship is unaffected by electoral outcomes, focusing instead on its pre-electoral dynamics. Our research note challenges this assumption by demonstrating that electoral outcomes can cause significant partisan shifts among voters. We argue that electoral losers are more likely to distance themselves from unsuccessful parties, while winners remain safely attached to the bandwagon. To demonstrate this, we first use household panel surveys from four European countries to establish that voters who supported declining parties are more likely to change party support in favor of gaining parties. Second, we show that individual-level partisan changes aggregate to meaningful public opinion shifts at the national level. To this purpose, we leverage monthly opinion polls for political parties across 17 European democracies and find that declining parties lose support among the electorate. Our results highlight a new dimension of post-electoral politics with implications for empirical research.